![[Snakeroot Organic Farm logo]](pix/sof.gif)

At dawn

Canoe bow waves are quickly lost

on the shoreside

But go on out of sight

on the lake side.

-1986

The constant swish-swish of skis

On a day long ski.

The constant swish-swish of wiper blades

On a day long drive.

-1990

My dog, trotting barefoot

Steps on a garden slug

And thinks

Nothing of it.

-1999

Word spreads quickly

as I approach the pond.

All becomes quiet.

-1997

Hidden in the vines

a large warted cucumber

jumps out of reach.

A toad!

-1997

Delicate puffs

of marshmallow snow

carefully perched

on a branch,

await the trigger of my hat

to melt their way down my back.

-2010

Deep in the tomato jungle

Fruits of yellow, purple and red

Tell of their readiness

To go to market.

-2010

Sugarin' Chores

Snowflakes hurry through my flashlight beam,

As my boots knead new snow with spring mud,

On my nightly Hajj to keep the boil alive,

For as long as possible until the dawn,

To match the power of the flowing sap,

With my meager evaporator and will.

The prize at the finish line are jars of syrup

And Spring.

-2013

Your Most Expensive Crop.

There's one crop almost everyone grows that is by far

the costliest

of all of the crops that are grown.

by Tom Roberts, October 2012

What do you suppose is the most expensive crop for you to grow? The one that requires the most labor, consumes great amounts of fertility and yet produces little to show for it?

Perhaps some folks think Sungold cherry tomatoes are a farmer's most expensive crop to grow. What with seeds going for over $60 an ounce, the hours of labor put into trellising, and dealing with un-sellable split tomatoes after heavy rains, the cost of producing Sungolds has got to be high. But there is an even more expensive crop to grow.

There is one crop almost all vegetable farmers grow that turns out to be their most costly crop to produce. This crop comes in dozens of varieties, some loving the cold wet spring and fall seasons, others loving the dry heat of high summer, while other types easily overwinter. The up-side is that the seeds are essentially free and no extra time ever need be taken to sow this crop. The down-side is that that it's labor requirements are huge and there is almost no market for this crop, regardless of its productivity and almost year-long abundance.

The crop I am talking about of course

is weeds. Deceptive little creatures at first, they soon rob the soil

of water and nutrients needed by your crops, and if left long enough

will also shade most of your crops from the sunlight that is the

power source for all green plants. Farmers spend considerable time and

significant expense combating weeds with chemicals, flames, hand

hoes, wheel hoes, tractor implements, hand pulling, mulches and cover

crops. Good farmers take the weediness of each field into account in

their annual management plans, anticipating the weed battles that

await them when growing each type of crop on each field.

The crop I am talking about of course

is weeds. Deceptive little creatures at first, they soon rob the soil

of water and nutrients needed by your crops, and if left long enough

will also shade most of your crops from the sunlight that is the

power source for all green plants. Farmers spend considerable time and

significant expense combating weeds with chemicals, flames, hand

hoes, wheel hoes, tractor implements, hand pulling, mulches and cover

crops. Good farmers take the weediness of each field into account in

their annual management plans, anticipating the weed battles that

await them when growing each type of crop on each field.

Although collectively weeds are

one of the greatest problems encountered by most row crop farmers,

true and lasting solutions to weed problems lie in looking at each

weed species individually. While all weeds do have some

commonalities, if we learn about the properties that are specific to

each variety of weed we can more easily gain the upper hand.

Although collectively weeds are

one of the greatest problems encountered by most row crop farmers,

true and lasting solutions to weed problems lie in looking at each

weed species individually. While all weeds do have some

commonalities, if we learn about the properties that are specific to

each variety of weed we can more easily gain the upper hand.

First of all, you need become acquainted with each of your weeds and their life cycle just as well as you know your crop plants. This task becomes slightly less daunting when you ask yourself “What are my major weeds, which weeds are causing me the most trouble and loss.” You begin by focusing on those.

Here is probably the most important

thing I have learned about weeds: The weed varieties that are giving

you the most trouble exist on your farm only because you have

developed farm management practices that are compatible with their

needs. You are managing for those weeds.  What types of soils you are cultivating, what kinds of

cultivation you do, what time of the season you turn the soil, what

cover crops you use, which crops follow which, how timely you are in dealing with weeds, what

crops you grow, and many other management factors all have an impact upon what

weeds you will encourage. Change your management practices a bit and

some of your weed species will simply begin to disappear. Change it in other ways, and other weed species will begin to disappear.

What types of soils you are cultivating, what kinds of

cultivation you do, what time of the season you turn the soil, what

cover crops you use, which crops follow which, how timely you are in dealing with weeds, what

crops you grow, and many other management factors all have an impact upon what

weeds you will encourage. Change your management practices a bit and

some of your weed species will simply begin to disappear. Change it in other ways, and other weed species will begin to disappear.

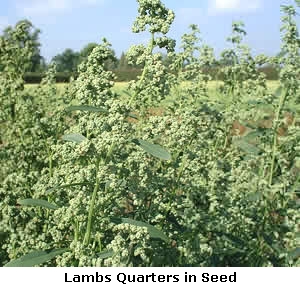

Begin by prioritizing your weeds according to how big a problem each weed is during each season. Perhaps you can say that in spring chickweed and mustard are a problem, while by mid June crabgrass and lamb's quarters become your focus of weed control. Then, every year take the top two or three and study them in detail. Learn at least these things about each one:

How many seeds to they produce, and when in the plant's life cycle? [Weeds that produce a crop of seeds only at the end of their life (lambs quarters, ragweed, amaranth) are not a propagation problem until then, altho they may become a production problem before then. Weeds that flower and produce seeds continually (chickweed, galinsoga, mustard) need to be removed as soon as, or even before, they begin to flower.]

How big are the seeds? [Small seeds need be very close (½ inch) to the surface to germinate; larger seeds can successfully germinate from greater depths (3-4 inches).]

How many seeds are produced? [Those that produce tens of thousands of seeds per plant (lamb's quarters, amaranth) need to be kept from going to seed at all costs.]

How long will the seeds remain viable if they don't germinate? [Some seeds live 60-100 years (lamb's quarters), while others only live 1-2 years (galinsoga).]

Are the plants frost sensitive? Heat or drought tolerant? [The morning after a hard frost all my galinsoga and crabgrass will be dead. Chickweed, the bane of spring and fall spinach growing, is hardly a problem at all in summer beets or carrots.]

Are they annuals or perennials? [Many perennial weeds will simply disappear thru normal management practices for annual crops.]

Do they propagate primarily via seed or via rhizome? [Exposing rhizomes (quackgrass, mints, sorrel) thru fall tilling allows them to winter kill. Rhizome-propagated plants can always be attacked thru slow tilling which produces many small pieces each of which has few reserves; follow this by several weekly light cultivations or hoeing.]

What soil type does the weed want? [Acid loving weeds (sorrel, cinquefoil) can be kept in check or eliminated by raising the pH of the soil with lime. ]

What you are looking for when studying your weeds is the weakest points in each weed's life cycle, that point of vulnerability at which you can attack it with simple changes in your management so that your major weeds become your minor weeds, if not disappear altogether.

You also need to be familiar with what each weed will do if ignored. Will that one lone new weed you discover become your next major weed problem if left alone to grow and produce seed? Any plot is 100% free of certain weeds, so be sure you aren't the one who first introduces those seeds.

Aside from “Know Your Weeds”, here are some other important weed suppression concepts:

Weed seeds. These are your future weeds. Do not let your major weeds go to seed, even if that means mowing or hand pulling. If they do manage to go to seed, try to remove them from the field rather than tilling them in. This may mean cutting the stalk at the base with pruners if they ahve grown large. Throw them in the woods or use them to mulch an apple tree or rhubarb patch (where annual weeds will never have a chance to grow). Weedy plots simply left un-tilled in the fall experience around 60% weed seed predation by birds and rodents during the lean winter months, so often spring tillage is preferred to fall tillage.

Rhizome Weeds. Several weeds reproduce primarily via rhizomes and relatively little via seeds. Rhizomes are underground stems that sprout new tops every few inches. Mints, sorrel, and quackgrass are examples. The plan of attack on these weeds is to starve the rhizome. Simply removing the tops by pulling or mowing only sets them back temporarily, since the rhizome left in the soil represents a storehouse of energy to re-grow the top. Tilling breaks up the rhizome and each piece will begin to grow as a new plant. Slow tilling (moving the tiller slowly through the soil) creates smaller pieces of rhizome. This will produce more new plants, but each piece now has less reserve to re-sprout. This is your first step in controlling the rhizome weeds. Continued cultivation or hoeing every week or two will prevent the newly grown tops from re-supplying the rhizome thru photosynthesis. Eventually fewer and fewer of the rhizomes survive. Rhizome weeds can also be damaged by fall tilling which leaves many rhizomes on the surface to dessicate during the winter.

Mulching. When mulching to prevent weed emergence, use a deep enough mulch to prevent any sunlight at all from getting to the soil; proper thickness depends upon the type of mulch being used. Check for thin spots, then patch them with more mulch. A too-thin mulch is sometimes worse than no mulch at all since you can't hoe out the weeds that grow through the mulch. Sometimes laying a thick mulch needs to be delayed until the crop is large enough or the soil warm enough. Large weeds that have grown meanwhile can be hoed or pulled, small weeds can simply be mulched over. Mulches do not stop all weed types, but will stop most of them. Mulching does not eliminate long-lived weed seeds, but it will stop them from sprouting and/or growing, and will cause short-lived weed seeds to perish if they can't sprout. Rhizome weeds can be controlled with a mulch by using heavy layers of cardboard or newspaper on top of the ground under the mulching material. See Combatting Quackgrass with Mulch

Weed seed bank. This is your total accumulation of weed seeds in your soil from past years of weed seed production. Of course you will want to stop making deposits into this bank by preventing new weeds from going to seed, but it is also a good idea to plan times in your rotations to allow these seeds to sprout and begin to grow. As soon as the field is in the “green carpet of weeds” stage, it can be lightly tilled to kill those and then allow more seeds to sprout. This repeated “fallow tilling” is the best way to rapidly deplete your weed seed bank. However, there will still be some weed seeds that will not sprout, as they are either too deep or are genetically programmed to wait for a certain number of years (or decades!) before sprouting. But this technique does eliminate nearly all of some weed varieties and greatly reduces most others. Note that doing this only in the spring or fall will not sprout your summer weed seeds, and vice versa! So either do a year long fallow, or a spring fallow one year and a summer fallow the next year.

Old Manure. Often considered “gardener's gold”, an old rotted manure pile may have produced a forest of giant weeds all around it—which year after year has allowed weed seeds to rain down on the pile. The same can happen to a poorly tended compost pile. Mix some of your rotted manure or compost with moist garden soil to do a test to see what sprouts. If it is very weedy you might want to restrict its use to perennials or to the bottom of holes in your garden, where the weed seeds will be too deep to germinate.

Watch the nitrogen. Many weed species are actually better at utilizing excess nitrogen in the soil than your crop plants are. So when you put an extra helping of compost on a field you can expect extra vigorous weeds. Like the Greeks discovered 25 centuries ago, “moderation is key”.

Light. Besides the right temperature and moisture, almost all weed seeds also need light to germinate. This is usually supplied by tilling or disking the soil, and the duration of light required for weed seeds to be triggered to sprout can be as little as 1/100th of a second.

Timing is everything. This cannot be stressed too stongly. Delicate little weed seedlings that today are easy to scuffle hoe in just a few minutes will become a major threat to the crop in a week or two and take hours to eliminate. Hoeing before a rain is about 90% wasted time, while hoeing in the early morning of a hot day is not only more pleasant but likely to be almost 100% effective. Hand pulling weeds that are about to go to seed and removing them from the garden so they can't recover can save you many hours of work over the next several years. If your crop is nearing its end of productivity and has almost no seed-bearing weeds, don't bother weeding it since soon the whole crop will be turned under.

Don't go for 100% weed free. It would be nice, but really it's impossible over the long term. Your goal should be no weeds seriously competing with your crops and none going to seed. New weed seeds will always arrive on your tiller or tractor tires and implements, your shoes, animal paws, bird droppings, imported manures, and some (miner's lettuce, milkweed, dandelion) will arrive on the breeze. The important thing is that when you see a weed, know whether it is important to get rid of it. Some of my minor weeds I simply ignore; they are not worth my trouble to bother with since there are so few of them and I know from observing them over years that they will remain minor weeds. On the other hand I pay special attention to some of my current minor weeds (milkweed, galinsoga, ragweed, velvetweed) and go out of my way to destroy them because they can become major weeds and would be were I not vigilant.

27 Organic Farm Road, Pittsfield Maine 04967 http://www.snakeroot.net/farm owned and operated by Tom Roberts & Lois Labbe Tom: Tom@snakeroot.net (cell) 207-416-5417 or Lois: Lois@snakeroot.net (cell) 207-416-5418 Gardening for the public since 1995. |

|

|